Jocelyn (The Reading World)

I love to read and can get very attached to my opinions, but recently I've been learning not to completely lose my head when people disagree with me, so feel safe to argue with me whenever you wish ;)

Political Order and Political Decay by Francis Fukuyama

Second of two in a series, following The Origins of Political Order. This covers history from the Industrial and French Revolutions onward, though it does take a brief projection beyond that in the section on the Inca and Aztec empires.

Fukuyama's thesis, put forward in the first book, continues to be central. The ideal government consists of three things: 1) a centralized state, 2) a rule of law, and 3) democratic accountability.

Being an American, I was most eager for the discussion of the United States that he promised to bring in the first book (why Donald Trump, why???). The attempt to take things from the long view, I thought, might help clear it up a bit. Why can't Congress get anything done? Why are our state bureaucracies so confusing, slow, and useless? How did this all come to be?

Apparently, it wasn't all bad. He highlights the beginning years of the Forest Service as a shining example of efficient and functional bureaucracy when Gifford Pinchot managed to keep it staffed by highly skilled, uncorrupt professionals. The American military has generally high ratings of approval, especially compared to Congress. A bureaucracy needs to have a certain degree of autonomous power and discretion to make its own decisions to achieve objectives for the common good, but the US never achieved it in its national government because it was founded on a distrust for an overly powerful state.

The chronology of how the three important components of government--the state, rule of law, and accountability matters. In the liberal democracies of Europe, it was the rule of law, the state, then democracy. In the United States, it was the rule of law, democracy, then the state. Since political participation was expanded beyond the educated, class elites to the masses before state institutions were fully consolidated in the Progressive Era and New Deal, political candidates and parties were able to appeal to short-term goals at the expense of long-term benefits. The government can't get too many useful things done without being lobbied and hampered by multiple competing interest groups, theoretically intended to give everyone an equal voice but in practice favors the most coherently organized and best funded groups. Today, that usually means large corporations.

As an example, Obama was only able to pass the Affordable Care Act by abandoning any role in legislation and making multiple concessions to congressional committees, insurance companies (among other groups I can't remember off the top of my head).

Another fascinating question I never knew I had was about the Aztec and Inca Empires. How was it that such large, impressive, and wealthy kingdoms were so easily toppled by European conquistadors? Multiple theories have been made: disease, superiority of weapon technology, the influence of geography (put forward by Jared Diamond's famous Guns, Germs, and Steel).

Fukuyama goes again back to his thesis of a universal pattern of political development here. His answer is that the Aztec and Inca Empires, though large and impressive, were actually not that far developed politically. His analogy is to China during its feudal period during the Eastern Zhou, prior to Qin Shihuang's unification in 221 B.C. Or India under the Mauryas, the unification of which did not last long. Unlike China in its more mature imperial period, the Aztecs and Incas lacked a unified written language and culture around which its people could coalesce to oppose European colonization. Power distribution resembled feudalism, decentralized around entrenched nobles that were not (yet) united around and fully loyal to a centralized state and made it easier for the European conquistadors to divide and conquer.

He agrees with Diamond that the north-south geography of longitude lines played a role in political development, but points out that the diseases took a toll on native populations after the empires of Mexico and Peru were toppled--finishing the job instead of starting it, so to speak. (I haven't read Diamond by the way, just FYI).

Finally, Fukuyama tries to explain why in the modern world after colonization, it is the Asian countries who have been most successful, and why that part of the continent was most successfully able to resist colonization.

Again, it comes down to institutions. China, despite its large population and diverse geography, has a long history of centralized state-building. It lacks an organically developed rule of law, due to the absence of transcendental monotheistic religions and lets the employees of its bureaucracy to manage things on local, municipal, and provincial level based on individual discretion and circumstantial context while still staying accountable to the national levels of power. Japan was ruled by the same imperial dynasty for over 2500 years and inherited its bureaucratic tradition from China, in addition to a unified language and culture.

The last element is especially important for one crucial ingredient for state-building: nationalism. Nationalism provides a narrative of legitimacy that further binds people to a country's state power. It also overrides any potential ethnic and racial divisions (not really a problem for China and Japan, both very ethnically homogenous countries). I can't remember much about the discussion of other Asian countries unfortunately, China and Japan is all I can recall.

Anyway, the result is that even after a brief period of submission and humiliation, China and Japan were quickly able to oust the Western powers, get back on their feet, and join the globalized world in their own right. Japan is a first-world country today, and the size of China's rapidly growing economy ranks among the top with the United States and European Union.

This is a big book...too much to cover completely here. I will say that I'm still slightly skeptical of Fukuyama's assertion of democracy as part of the inevitable ideal of political development and wish he'd gone over more thoroughly the many times in recent history in which exportation of democracy completely failed by the United States in Iraq, Afghanistan (can't remember them all) as a counterbalance to his thesis. He acknowledges that "getting to Denmark" is a path that must be built on indigenous traditions, but it still feels like there's a stronger point to be made when the points in this book are applied in practice. Isn't it possible that developing countries are forced to take risky institutional gambles in the name of Western ideological perfection before their national identity, ability to eat, ability not to have civil wars etc. are fully consolidated? Hasn't it already happened, in fact? That's just my point of view, and I don't disagree with Fukuyama (one look at his bibliography and he's obviously WAY better read than I am). Overall, one of the more interesting works I've read in a while.

Dust in the Desert by Starla Huchton

BL doesn't have a page for this book, but here is the GR page.

And the cover:

The premise is deeply intriguing: a gender flipped retelling of Aladdin. I was drawn at first to the beauty of the ancient Middle Eastern setting, the POV of a plucky female thief, and the prospect of a smart-alecky female genie (no dice on that one, but it's ok). Huchton did and continues from what I've skimmed to score points on the setting, landing this book firmly in the saved-for-a-rainy-day-with-nothing-else-to-read camp.

But characters make or break a story for me, and while it was tolerable in Shadows on Snow I found myself rolling my eyes far sooner than I anticipated or desired.

So the general plot is fully kicked off when Alida decides to trade her life in return for that of a criminal falsely accused for the crime she committed, and what do you know...yep, this is what gets the prince to fall in love with her.

His golden gaze lifted to mine, an awed confusion in his expression. "For four days, all I've been able to think about are your words in the square. You could've been free if you stayed silent. Why would you step forward that way? Why forfeit your life?"

All my suspicions of Alida's specialness were confirmed when it turns out she's secretly royalty and the destined heir to overthrow the evil queen. (Sorry for the spoilers, but this is like the oldest fantasy cliche in the universe...no one could not see it coming.) At this point, the long-lost backstory started surfacing and overtaking the plot, I started to get bored and commenced the skimming.

A little while later I found this, when she reunites with the prince again:

Seeing his grief, my heart ached for him. It must've been horrible for him, thinking me dead, still hearing the scream the red feather man stole from me. Even I shuddered at the memory.

Just to top it off though, he has to reminisce about how awesome and beautiful she is (who remember, he knew for three days) in front of her, who he doesn't know is her

"I'm not any less angry about so much wasted beauty."

I tried not to, but I started a little. Beauty? Not once had I considered myself such a thing. "You...thought she was beautiful?"

Sameer visibly cringed. "I mean...Well, yes, but not..." He scrubbed at his face and turned to me, taking my hands in his. "When I said you remind me of her, it isn't in the way you look. The beauty she possessed is the same I see in you. There's something in your spirit--a kind consideration, honesty, and wit--that feels so familiar to me, when you speak I wonder if you aren't perhaps the same person."

I know it's a fairy tale, but honestly, who talks like this? I'm sure if the story had remained faithful to the original gender roles, the woman wouldn't be reminiscing about the man's "wasted beauty." Talk about putting someone on a pedestal.

I am still interested in giving Ride the Wind a try because I love the "East of the Sun and West of the Moon" fairy tale to death, it's quite possibly my favorite. I also loved Jessica Day George's retelling in Sun and Moon, Ice and Snow, so I have something to compare it to as well.

Shadows on Snow by Starla Huchton

Gender flipped Snow White:

Evil stepmother queen-->evil stepfather king

Beautiful princess with black hair/pale skin-->handsome prince with black hair/pale skin

Seven dwarves-->seven sisters, one of whom is the love interest and protagonist.

I wish I've read more Snow White retellings besides the original fairy tale the Disney movie to compare this to, but I have not, except for Fairest which doesn't count as a traditionally faithful retelling for me.

The magic reminded me a lot of Uprooted, sinister and dark on one hand, wondrous and beautiful on the other. One difference would be the amount of exposition. Huchton doesn't explain much, and I liked being forced to intuit the workings of the world for myself. Another would be that the main character, along with her siblings, also has a specialized inborn skill. I would guess that this is the equivalent of the seven dwarves each having an individual trade.

Characterization, especially the romance, was weakest part of the book. Maybe I'm being too sensitive, but there were a few too many times of this:

"That is a person with a truly lovely spirit. You are filled with beautiful things, Raelynn."

Blah...kind of ruins the magic, if you ask me. The non-Snow White retellings I've read tended to have decently developed relationships, so I know it's not impossible.

But this succeeded in pulling me along quickly and creeping me out on the moments it needed to. Occasionally unrealistic dialogue detracted from the sense of wonder just a little.

Beloved by Toni Morrison

I think I appreciate this a lot more than I love it. Even then, by the time I was 100 or 200 pages in, I wished I'd paid more attention in the beginning so I could have grasped the structure of the story better.

Shortly put, Beloved deals with the effects of traumatic memory on the present. The way institutional change does not mean immediate emotional change. We are, of course, talking about American slavery: eight years after the end of the Civil War in 1873, Sethe and her daughter Denver struggle to build their lives in freedom, even though Sethe is still haunted by her past and Denver's emotional development as a young adult is stunted because of it. The main, though definitely not the only, source of trauma: years ago when slave catchers came to retrieve Sethe and her children after they'd run away, Sethe attempted to kill them rather than allow them to return to slavery. She succeeded with her second-youngest baby, Beloved. This part of the plot has historical basis in the story of Margaret Garner.

I'm not sure what there is to say. It feels like the kind of book that set out to express the un-express-able. Maybe before this, I simply couldn't imagine what it must be like to have mind and body completely under someone else's control...and to still feel that way even after being given freedom. It reminds me of how modern abuse victims struggle with being trapped in the emotional lifestyle that they had to adopt in order to survive. The things normal people take for granted: a basic sense of self and physical safety, an education, a hope for the future, are made to feel completely unattainable. More tragically perhaps, the trauma is not limited to one generation: Denver is all but robbed of her childhood because her mother and the community that should have taken care of her have enough on their hands trying not to let their pasts take over them. And it's not really explicitly stated, but the subtext does prompt your imagination a little. How coldly impersonal an institution slavery is: nationwide, systematic, and taken down not because blacks themselves were able to mobilize as a group but because people already politically privileged enough were able to legislate its removal.

It's an ugly period of history to write about. After the Reconstruction, blacks had to wait almost another hundred years before their voting rights were given full protection. The concept of a single group of people prevented from reaching full self-determination for generation after generation is just mind-boggling, and the fact that it's so recent in national memory begs the question of race relations today. Luckily for us, Beloved does conclude with a happy ending.

Paused

This book, the first of an ongoing series spanning almost the entire recorded history of China, goes over four chronological periods: Shang dynasty, Zhou dynasty, Spring and Autumn Period, and the Warring States Period, all the way up to Qin Shihuang's unification of the empire in 221 B.C. I chose it for several reasons:

a) it's written by a number of trained Sinologists, some rather famous, so I was ensured a certain level of expertise and credentials. All of them are probably fluent in Classical Chinese, which means primary sources are accessible to them,

b) it alternates between textual and archaeological history in balance to one another, guaranteeing a critical look at historiography and bypassing the effects of either nationalism or Western-centric criticism, and

c) I was looking to build a narrative history of the pre-imperial period and a book almost 1100 pages long was guaranteed to have some points coherent enough to string together.

But, it should be noted I haven't read the whole thing (yet). I read way too slow and I won't be able to check stuff out at my school library for another three months. Here are the chapters I did read, crossed out:

1. China on the Eve of the Historical Period

2. Language and Writing

3. Shang Archaeology

4. The Shang: China's First Historical Dynasty

5. Western Zhou History

6. Western Zhou Archaeology

7. The Waning of the Bronze Age

8. The Spring and Autumn Period

9. Warring States Political History

10. The Art and Architecture of the Warring States Period

11. The Classical Philosophical Writings

12. Warring States Natural Philosophy and Occult Thought

13. The Northern Frontier in pre-imperial China

14. The Heritage Left to Empires

I am very excited to read 13 and 14. All the others left remaining...eh...not so much. But I might slog through it just to be proud of myself.

For any future readers, my advice would be to customize this book to your interests; I regret not going over the table of contents more thoroughly beforehand. I was most interested in political and military history of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Periods, but still went through the first 500 pages (Shang and Zhou) before getting even close. The nature of a time period so distant--2nd and early 1st millennium B.C.--means this book is forced to extract a lot from very little. The main source of study in that period are the Shang oracle bones and Zhou bronzes, so you don't get so much a "story" as you do pages upon pages of hypothesizing and examination of obscure archaeological objects. There's also a few other drawbacks: this was published in 1999, the incorporation of archaeology into Western Sinology is actually quite young, so new discoveries being made at the present moment of writing could very well mean this information will be outdated in the near future. (In fact, the introduction explicitly states that the writers of this book hope it will become outdated if archaeology continues to proceed at its current pace.)

It's expert stuff and as accessible as it can possibly be without being able to read the archaeological inscriptions yourself. If you have massive and divine powers of concentration, which I definitely do not, this will be very rewarding.

Anyway, after struggling through what was undoubtedly beyond my level of comprehension and only a little within my interest, I finally decided to skip to what I was really looking forward to: Chapter 9, the political history of the Warring States. Actually, what I really wanted to read about was the development of the military strategic tradition, and I did stumble upon a few measly gems:

The commander also figured, along with the "persuader," as one of the archetypal figures of the realm of stratagem and cunning. The military treatises describe the ideal commander as a potent figure who could penetrate the flux of appearance, perceive underlying order, recognize decisive moments of change, and then strike. He was able to disguise his intentions while penetrating the schemes of his adversary and to manipulate appearances so that the enemy would march to its doom. A master of maneuver, illusion, and deception, he waged war in the realm of the mind and directly translated his strategems into victory in the field.

Oh yes. ...Although the fact that I had to hunt through a tome as big as this for so little really says something about how many damns Sinology gives to military history, compared to the pages upon pages of cultural, linguistic, archaeological, and philosophical analysis. Sigh.

This does bother me on a more than personal level. I feel like a lot of pre-imperial history doesn't make sense without getting into logistics, especially in a time period most famous for its warfare. Were ancient Chinese armies really as big as they're reputed to be (hundreds of thousands)? If so, what made it possible? And the passage cited above is tantalizing for its lack of information. Which generals exemplified the ideal described? Which military treatises? What victories on the battlefield could be traced to operational and tactical genius, especially the final Qin conquests? Yet another interesting thing to delve into would have been the civil engineering projects of the Warring States Period, spawned by the military competition between states at the time, but topics like Dujiangyan irrigation system which made the Sichuan basin one of the richest regions in the Chinese subcontinent--and is still in use today--are mentioned only in passing.

It might sound like I'm complaining a lot. I am, actually, but not just about this book in particular. Western and Chinese collaboration on Chinese history is a relatively new thing that only started seriously taking off in the mid 1900s. The authors had and have a gargantuan task ahead of them, and the mere concept of a project like this simply takes my breath away, let alone what it would be like to read the whole series. I think I'll somehow manage to get through the rest of this book and can't wait to read the next volume on the Qin and Han empires--a time when indigenous Chinese historiography became a discipline in and of itself. (hopefully fewer bronze vessels to analyze). Hopefully they have something at least passably juicy on the Han-Xiongnu War.

The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb: Hiroshima and Nagasaki: August 1945 by Dennis Wainstock

Another short, condensed synthesis of the decision to drop the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Wainstock delves into a lot of intimate details on both sides of the war, including quotes, messages, radio signals etc. as well as the U.S.'s shaky relationship with the Soviet Union. I don't remember much of it unfortunately, and I'd assign more importance to specific pieces of evidence if only I was actually deeply interested in this topic.

One thing I do remember is that Wainstock focuses a lot on how revolutionary it was for Emperor Hirohito to intervene with the Japanese Supreme Council when it came time for Japan to surrender to the U.S. The Council needed a unanimous vote in order to agree to surrender, against which the military faction was strenuously opposed even after the double blows of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, let alone the Potsdam Declaration. The Potsdam Declaration itself contained a particularly contentious Paragraph 12, which set vague terms of unconditional surrender and left the Japanese unsure of whether they would be allowed to retain the institution of the emperor.

In Wainstock's opinion, the U.S. was unreasonable in allowing so short a period of time--three days after Hiroshima for the bombing of Nagasaki--to allow the Japanese to adjust their policy accordingly. Moreover, the U.S. should have made it explicitly clear that the Japanese would be allowed to retain their emperor; thus, careless ignorance of cultural differences factored into the decision.

This is the second of two books I've forced myself to read on the subject. Both were very scholarly, very concise, and very dry--excellent for compilations of evidence, but not much in terms of working out the moral justifications of the bombing. I wonder what it'd be like to read from someone with a passion and enthusiasm for this. Or maybe it's a younger topic than I'd previously thought and has yet to produce conclusive analysis.

I'd personally think that the U.S. embargo, bombing of Pearl Harbor, and U.S. expectations of the Pacific War would play a huge role in deciding the sincerity and necessity of the atomic bombs, in addition to the damage already done by conventional bombing, but so far I've only seen it explained as not much more than background. It seems like Truman was genuinely concerned about resolving the war at the lowest possible cost to American lives--could any president look his people in the face and confess that American soldiers had died to spare the enemy when they had an expensive weapon of mass destruction at hand to end it?--but whether the U.S. under Roosevelt provoked the Pacific War with full prior expectation of Japanese attack, is still very unclear to me.

Paladin by Sally Slater

Lightly written and lightly enjoyed. I don't really have a thing for scary otherworldly creatures (demons), but the highlights in the characters provided nice counterpoints to one another.

Plus, the sword-wielding teenage heroine disguising as a man trope never gets old. There were many, many, many times when it got this level of tense:

...and my classmates would stare at me funny as I giggled uncontrollably with my eyes glued to my Kindle.

I think a more memorable book would have gone deeper in the emotional resonance scale. The action scenes felt repetitive and lacked tension for me because the enemy (again, demons) were so inhuman and never inflicted lasting, or at least believably lasting, damage. Braeden's character is the old "struggle against my inner monstrosity because I'm half beast" trope that seems set up for a dead end: if his humanity wins out, we already expect it, but if the monster side wins, there's not enough at stake to invoke any sort of tragedy.

Possibly the most nuanced bit of characterization is when

We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

I watched the TED talk here:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hg3um...

And read what I think is the shortened pdf here:http://jackiewhiting.net/AmStudies/Un...

_________________

Some people ask: “Why the word feminist? Why not just say you are a believer in human rights, or something like that?” Because that would be dishonest. Feminism is, of course, part of human rights in general—but to choose to use the vague expression human rights is to deny the specific and particular problem of gender. It would be a way of pretending that it was not women who have, for centuries, been excluded. It would be a way of denying that the problem of gender targets women. That the problem was not about being human, but specifically about being a female human. For centuries, the world divided human beings into two groups and then proceeded to exclude and oppress one group. It is only fair that the solution to the problem acknowledge that.

I must admit, there was a shameful (but thankfully brief) period in my life when I was one of those who tried to put distance from the word "feminist." And that was after another extended period when I was proudly and openly feminist. So three stages so far for me:

feminist-->uncomfortable closet feminist-->feminist again.

To be honest, I think it gets humiliating to defend your dignity after a while. To say unequivocally, "I'm a worthwhile human being" and have people tell you to stop making a fuss. Stop playing the gender card. Stop playing the victim. How ironic that suppressing expressions of anger and dissatisfaction because of its association with being "unfeminine" is a classic tool of patriarchy.

It's also kind of ironic given my own past of momentary doubt that nowadays, I'm extremely wary of "explaining" feminism because...well it's not my job to educate you dude, what about feminism isn't blatantly and painfully self-explanatory?

Why is it that a movement with a grand history of giving women

1. the right to divorce

2. the right to own property

3. the right to vote

4. the right to higher education

5. the right to abortion

6. protections against rape and domestic violence

7. the right not to get fired when you get pregnant or married

8. etc. etc.

...have so much stigma attached to it?

Who wouldn't be proud to call themselves the inheritor of such a legacy?

How many brain cells do people have to string together before realizing that the label given to this awesome history, and is still ongoing--called feminism--is a good thing?

So I don't know if it's a mistake or not to sarcastically roll my eyes every time I talk to someone (usually a male) about why feminism is important. Or when someone takes it as a given that a woman dressed in revealing clothing will get raped and we should all be "realistic." (For that matter, I think feminism is inherently idealistic, and that's what gives it its greatest appeal.) I just can't decide if it's worthwhile to compromise time and energy on the off-chance that maybe someone with pile after pile of internalized misogyny will bother to sit down and do their homework before making blanket statements on a movement that has had a spectacularly positive net effect on the world and is still doing so today. Because if they did then we wouldn't be having this conversation in the first place.

Maybe I can just give them this essay instead?

Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking

Reading this was like the best part of reading the Internet. A bunch of disparate, outcast-ish voices coming together for the common cause of relating their experience. Of course, this is more than just anecdotes. I loved how meticulously Cain moves from issue to issue, question to question, so almost nothing is left unanswered or unexplored. We know that extroverts and introverts are a thing. How does free will come into play? Nature versus nurture? How do pseudo-extroverts (introverts who put on a mask of extroversion to survive in society) manage to wing their acts? To what extent can we consciously mold our personalities and to what extent are they inflexibly innate? Is the social emphasis placed on extroversion universal across all cultures? How did the Extrovert Ideal emerge historically?

And most importantly (to me), what survival advantages have introversion conferred on the people who call themselves so that allowed it to pass the test of evolution?

Yes, that last question is very important to my ego. Although if I'm being honest, I wish introversion wasn't so much celebrated as it's understood. That we can't choose who we are, but given the right circumstances, we can all thrive to the best of our potentials.

If there's one thing this book didn't do for me, though it's not necessarily Cain's fault, it's that I still don't understand a thing more about extroversion. Living in a community of extroverted classmates, friends, and family members, I know enough about the patterns of extroversion to get through the day. But I don't--can't--empathize with them. I don't get the partying, the tendency to skate from activity to activity, the love of socializing, the breathtaking ease with which my extroverted peers "participate" in class. And most of all I DEFINITELY do not get the small talk. Oh, the small talk. *gag* Surely introverts can find a way around that someday?

Ok, aside from that unintended little rant, I think this is a lovely and well-researched book.

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Well, this counts as my fourth "Great American Novel" after Catcher in the Rye, Huck Finn and Moby-Dick. (Wow, all male-centered...hmm...) Surprisingly, it was also the most emotionally resonant. I *think* I got the subtext, and I did love--occasionally--how much it felt like a relic of a lost period in time. The prosperity of the Roaring Twenties, the Jazz Age, the elusiveness of the American dream. Much of it revolves around Gatsby's emotional bankruptcy, which makes me think this would be an awesome book to read during a crisis.

I just...I dunno. Maybe it's the book's iconic popularity that annoys me to some petty degree. I wish I didn't have to have read it for school. Then again, I'm not sure I would have picked it up of my own accord. I wish I could say it's irrelevant to my life, but the way Americans constantly hoot about pulling yourself up by your bootstraps would say otherwise. I admire the way Fitzgerald proves this wrong in every respect, not only financially but also in terms of a completeness of self-esteem that Gatsby will never able to gain for himself. It's the ultimate tragedy that resonates, but still leaves me unsatisfied. It feels like we're expected to accept everything, class shittiness and all, with nothing else than an exhausted shrug. I'm not that pessimistic yet.

The Tiger Queens by Stephanie Thornton

I'm sure no book quite like this has ever been written before.

"I still carry the curse I once warned you of," [Borte] finally said. "Would you bring a storm of death onto the steppes?"

Temujin shrugged. "My strength in battle has already been tested. With you as my wife I will become a great and powerful khan, and our children will multiply and rule from the Great Lake to the Great Dry Sea."

Tiger Queens is a historical epic that stretches almost eighty years from 1171 C.E. to 1248 C.E. Timeline wise, the one that most of us are most familiar with anyway, this starts with the future nine-year-old Genghis Khan and ends with the crowning of his grandson Mongke Khan, placed three years earlier than the historical date for plot purposes.

But first and foremost, this story is one that belongs to the women. Which is why I read it (duh). They say that behind every great man is a great woman, and if this book isn't a splendid homage to that then I don't know what is.

Four perspectives placed one after another in succession: Borte Ujin, Genghis's empress; Alaqai, their youngest daughter; Fatima, a Persian captive; and Sorkhokhtani, Borte's daughter-in-law and mother of Mongke and Kublai Khan. The overarching plot driver is Genghis himself--who against all odds, survives his childhood, defeats his rival Jamuka, and unites the steppes before looking outward for civilizations to bring under his rule. But at home, it is the women who make sure his kingdom stays intact, and band together to rescue it when his male successors find themselves at each others' throats for the throne of the Mongol Empire.

The scope necessarily makes it an extremely fast-moving book, which is part of the appeal. The passage of time literally almost feels like the wind, quite appropriate considering how quickly the Mongol Empire consolidated itself from a group of scattered nomad clans to the largest contiguous empire in history. Time is especially condensed towards the last third of the book during Fatima's perspective. As the only foreigner in the group of four, her view is important because it's such an emotionally transitional one: as a new captive she's repulsed by the Mongols' barbarian savagery, before years and years pass and her thirst for revenge changes to the loyalty of a sisterhood.

Childless, and without a mother, father, or husband, I had no one in this world. Yet Toregene had been by my side for half my life, a sister not of blood, but of circumstance.

Second to Fatima, the most fascinating perspective for me was the first one, Borte's. I'm quite intrigued by Thornton's use of prophecy as an accurate plot predictor of death and destruction. It's definitely not enough to call it a fantastical element, but it's so eerily woven into the structure of the plot. Blessed with the gift of foresight, Borte sees that she'll precipitate a bloody war on the steppes, and this does indeed come true with Genghis's conflict with his blood brother Jamuka. Borte's POV also gives the largest coverage on the theme of sexuality, dynamics of gender, and the astonishing cruelty inflicted on women of defeated clans. With every conquest of her husband, there is looting and there is rape. Men are killed while women are absorbed, some whose new families extinguish the desire for revenge, some whose marriages give them newfound power comparable to that of their husbands'.

Alaqai's and Sorkhokhtani's stories are mainly ones of survival--the last ones standing. I should give a warning as Sorkhokhtani's section is surprisingly short, only taking up the last 60 pages or so compared to the hundreds of pages devoted to the three other women. It's no less important for that, in part because it was such a momentous point in history, and everything I'd ever assumed about Mongke and Kublai Khan as historical figures gets turned upside down when I realize that there was a mother behind the scenes biding her time and pulling strings. Thornton's author note at the end provides additional information. I'm more convinced than ever of Thornton's central principle--that the great men of history could never have accomplished what they did on their own without the help of women.

In sum, if Borte Ujin, Alaqai, Fatima, Sorkhokhtani, and Genghis Khan themselves were to time-travel to the present and read this book, I'm certain they'd be nodding their heads in enthusiastic approval.

$2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America

$2.00 a Day is my first serious attempt to dig into present-day social realities, and I'm lucky to have found it comprehensive, concise and rather powerful. Much of that power comes from the way the book works from the ground up, from the daily realities of $2-a-day poor--which takes up the bulk of the book--to viable policy proposals on the federal level that make me wish these authors were participants in Congress.

Up until 1996, Lyndon B. Johnson's "War on Poverty" created the most robust government programs for the poor up to that point in history with the Great Society, expansion of Social Security, Medicaid and Medicare. Thus came into being a conflict in American values between compassion for the poor and the belief in economic autonomy. When David Ellwood attempted to defend welfare in the public spotlight, he was met with astounding backlash, prompting him to formulate a multidimensional proposal based on publicly funded work opportunities, a raised minimum wage, and high-quality education and training programs--components he believed aligned with American values and were more likely to win the public's approval.

Then came the presidency of Bill Clinton and a Republican-controlled Congress. Long story short, Ellwood's plan--long admired by Clinton--met with opposition among policymakers and ended up being thoroughly repackaged. Federal welfare funds were given to states in the form of block grants, but with strict requirements in workforce participation that states managed to meet by slashing assistance when its allotment of funds ran out. Though lower unemployment rates signaled success of the reform in the public eye, the poor continued to suffer, relegated to low-wage jobs in the service sector where fierce competition left (and still leaves) prospective employees vulnerable to exploitation. The majority of these jobs are usually unstable, unsafe and insufficient to provide for even the most basic of material needs: food, housing, clothing, and least of all a modicum of dignity.

What follows is a series of personal stories. Believe me when I say it is soul-crushingly depressing, least of all because the primary cause of $2-a-day poverty is a mismatched scattering of resources--not personal laziness. The path to poverty is a downward spiral. Don't have a car to make it to your job interview? Take public transportation. Wait, no cash? Then you have to walk...twenty miles across the city and show up late. Oh, you're late? That means you're not a serious employee and your chances are out. Trudge back home--assuming you have a home, or a homeless shelter that will evict you within three months if you don't find a job--and start over from nothing. From a string of nothings, over months and years and decades.

I also thoroughly appreciated this book's focus on women and single mothers. Not to sound like a raging feminist...again...but gender inequality does get dramatically worse the farther down the social and economic ladder. Single mothers, particularly divorced or those who never married, are the victims of huge social stigma. One of the most heartbreaking stories was that of Tabitha, who in 10th grade enters into a 7-month sexual relationship with her gym teacher in exchange for food. (He was never prosecuted.) Modonna trades sex with a "friend" for food and shelter, but when she defends her daughter from said "friend's" growing sexual attentions, the mother-daughter pair is thrown out into the streets.

To repeat what other reviewers have said, this is an important book and one that I'm heartily glad to have read. It's probably going to hang over for quite some time, but I think I need it.

Daniel Deronda by George Eliot

Well...I've let this one sit for weeks and can think of nothing to say, because the book already said everything. Except that my overwhelming impression of my first Eliot is that it is very, very feminist.

Plot details aside, this book made me think that one of the biggest obstacles women face is the complete inability of a society to imagine that they want more for themselves. The tragedy of marriage being a woman's only respectable option is felt most passionately through Gwendolen's and

thwarted ambition. Gwendolen is at the height of her spirited youth at the time of this book, but with the latter character, you can really see how the misogyny of a patriarchy unfolds itself over decades and it's nothing short of devastating.

Mr Grandcourt defied all expectations, for the main reason that his power struggle with Gwendolen was so pointed and personal. They are clearly emotional and intellectual equals in every way, but Grandcourt's position as her social superior turns their marriage into a speedy and crushing conquest. He does it just enough to leave Gwendolen with a flicker of defiance, for a master's satisfaction of squashing it all over again. As poignant as Gwendolen's sorrow is, this almost makes me think that Grandcourt deep down actually respects her, even if he doesn't hesitate to keep her in second-class status.

Deronda's plot thread was much more challenging, especially when he starts exploring Jewish culture with Mordecai. Sometimes those conversational passages would get so dense I'd put the book down for days before coming back to inch through one page at a time. I had a much easier time with his interactions with Mirah and the Meyricks, Sir Hugo Mallinger, and of course Gwendolen. Still, it's an involving story. The combination of his curiosity about his parents, his search for identity, and his tentative role as Gwendolen's first moral guide added a breath of worldliness for me. I was pretty intrigued by the structure of a double storyline in the first place, and the subtle ways they're linked thematically as well as physically lived up to those expectations.

I'm not sure what made me pick up this over Middlemarch as an Eliot starter. It could be I had a better idea of the plot beforehand. This book is also epic in scope, stretching over a lot of western Europe and even across the Atlantic Ocean all the way to the States. And though I've heard that the "spoiled brat" is a common character in Eliot's works, I also wanted to see for once a sympathetic portrayal, not a sexist stereotype. I wasn't disappointed. I'm not sure the next time I'll be ready to dive into another equally deeply involving work of Eliot's, but when I do, I'll expect to be as moved by the humanity and uncompromising assertion of dignity as I was by DD.

The King of Attolia by Megan Whalen Turner

I wish this book was much longer so I could keep reading and reading and reading. It's arranged almost like a series of short episodes, and Turner's decision to use marginal characters for POV kept me dying to know about Eugenides with whom we've always been much closer. What's Gen thinking? Planning? Doing? Sneaking? But we get a lot of his sarcastic personality through dialogue, which satiated my curiosity by the end.

Since every book has provided a change in perspective, scope, and method of character development, now I'm curious to know how A Conspiracy of Kings is going to go down. I loved the geo-political conflicts of The Queen of Attolia, but this book in the circumscribed setting of the royal court was more on-point with the wit.

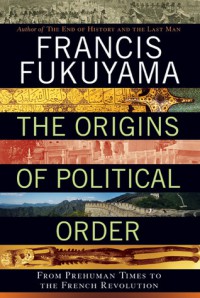

The Origins of Political Order by Francis Fukuyama

This is my first foray into political science, which maybe explains why I took so long to read it. Occasionally, I got lost in Fukuyama's analysis until his thesis reasserted itself. In retrospect, it's an impeccably organized book, comparing the history of political development in four broad geographical areas: China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe.

China is examined first, with the justification that it was China who first invented the modern state. With the Western Zhou dynasty in the first millennium BC came the rise of feudalism. That is, de facto power was split among several self-sufficient lords and the king mainly held ritual power. Over the course of several centuries, the territories emerged as states in their own right. This process was prompted through extensive warfare, motivating rulers to increase the size of their bureaucracies and mobilize ever-larger numbers of the population during the Warring States Period. Hundreds of years later, Europe would go through the same process, the main difference being that European period did not end in national unity as China did with the Qin empire.

Next Fukuyama examines India. It should be noted that one of the book's major assumptions is that the trends for present-day politics were laid thousands of years ago at the roots of a region's civilization. Unlike China, India never developed a powerful, centralized state because of one major reason: the caste system. The stratification of society was strong enough to oppose any force that could override the separation of the Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and Shudras. This legacy endures today in modern Indian democracy, where multiple interest groups block the efficient passing of legislation and the strength of society exceeds the strength of the state.

For some reason, I remember a lot less of Fukuyama's discussion of the Muslim world other than two things. The first was the institution of military slavery, created to counter the fundamental aspect of human nature that favors kinship at the expense of centralized state power. The second is that Fukuyama uses the initial growth of Islam after Muhammed to illustrate a war for "recognition"--that is, the acknowledgement of status and worth--as a refutation of the idea that all human conflicts are fought over a few essential economic resources.

Lastly comes Europe. According to Fukuyama, the exit out of tribalism--a universal stage in political development across all cultures--occurred through Christianity, forming a strong social counterweight to the power of kings. As a mobilizing force, it instilled a loyalty to religion first, and family second. At this point, it's either me being muddleheaded or Fukuyama's analysis blurring together; many distinctions are made between Western and Eastern Europe, but other than the development of serfdom in the latter, I can't remember. Someday, I'll have to reread this section as well as the Muslim one.

One fascinating topic that Fukuyama sets out to answer is the question of what makes the most successful form of government. His thesis sets forward three separate institutions:

1) the state, or monopoly of military power over a defined piece of territory

2) the rule of law, a written body of rules whose legitimacy transcends generations

3) accountability, the subordination of sovereignty to the will of the people

In terms of historical timeline, institutional change is slow, resistant, and bloody in the end. Even in the most dysfunctional systems, there will be existing stakeholders who block institutional change because of the threat of personal loss. In this instance, the threat of violence is often the most viable path forward. This was how China and Europe developed state efficiency. How present-day regimes suffering from corruption can resolve this issue is a topic that is touched upon, but probably expanded on further in the sequel, to which I look forward.

Now if somebody could hand me a military strategy version of this book, I would be very happy.

Set aside

A number of factors made me set this aside at around page 144, the major one being it's due back to the library in a few days. A precious week of break and I'm determined to hoard it for other top-priority books.

But also, it's not holding my attention with that basic, irresistible desire to find out what's happening next. First, there's no faster way to dissipate my interest than to stuff a woman in the fridge and have a guy mope about it for years afterward.

So I skipped to Mai's storyline, the real reason I started reading Spirit Gate. For some time I enjoyed trying to match up the blushing virgin of this book with the sexually confident, mysterious woman of Black Wolves. I still really, really want to know the full story behind Mai's relationship with Anji.

From Black Wolves, I'm guessing Elliott likes to start things slow and go with a snowball effect, by which the story gradually accumulates momentum. Thus the ultimate question, do I indulge my short attention span by giving up, or do I swallow my impatience and follow through with what seems laborious now but possibly rewarding in the end?

I don't have the time or mood to pick the second option now, but maybe someday.

1

1

4

4