Jocelyn (The Reading World)

I love to read and can get very attached to my opinions, but recently I've been learning not to completely lose my head when people disagree with me, so feel safe to argue with me whenever you wish ;)

The Lotus Palace by Jeannie Lin

I think this is the most romantic of Jeannie Lin's books I've read so far. All the other ones seem to be so forbidden all the time, stolen moments of bliss against a situation of how the relationship would never be accepted by society. Sure, this has that too, but it takes some time to get there. The first fourth of the story: flirting, courtship, wooing with gifts. Quite sweet actually, with Yue-ying's stubborn practicality and Bai Huang's privileged fop attitude.

Then finally, mutual familiarity and closeness is accepted, and worries about social class, money, and reputation take over. The tension between the two lead characters from Bai Huang's social advantage over Yue-ying is delicately explored, and I could imagine that hundreds of years ago in the late Tang dynasty, an aristocrat and a former prostitute could grow to love each other as equals.

My other favorite relationship is the one between Yue-ying and her sister, the beautiful courtesan Mingyu (who features as protagonist in the sequel The Jade Temptress). It's a complicated relationship arising from their separation of ten years after being sold by their parents, reunited after Mingyu managed to buy Yue-ying's freedom and bring her home as a personal attendant. Still, they pick up the pieces as best they can and remain dedicated to one another, united in a dream of one day having more choices than those available to a courtesan--in reality a glorified sex slave--and the sister she watches over.

There is something about this story that feels very sensitive and emotionally nuanced, while The Jade Temptress is daring and seductive. No one can top a twisted suitor as a villain surely.

Jeannie Lin is fast becoming one of my go-to authors and I'm debating which book to go after next. I am very angry that no library in my entire county stocks her steampunk series. Ugh!

Modern global history still gives me a headache, but...

Only read this if:

-you are a student trying to write a research paper

-you know nothing about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Ok, just kidding. The two criteria definitely fit me, though. Hence this book, and taking almost two weeks to slog through the first 68 pages, before taking a deep breath, telling myself to suck it up and churning through the remaining 34.

For such a short book, Walker packs a lot of information and analysis. I'm impressed, although I was annoyed at first that Walker seemed so intent on restraining himself from passing a moral opinion. Mostly because I thought it made the book waaaaaaaay too dry. As the book went on and more evidence was examined, I started to appreciate his attempt to bridge both sides of a debate that even ignorant me knew to be extremely polemical. In fact, I started this thinking that NOTHING could ever justify the bombings of Japan.

This is a very narrow work, and spends most of its time analyzing the situations and concerns facing Truman and his advisers up to the eventual bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the primary one of which was to end the war as quickly as possible at the lowest possible cost to American lives. This was an objective first set forward by FDR before he died and passed the presidency to Truman. The second was the Manhattan Project--the development of the bomb itself--which had been kept secret from Truman until FDR's death, requiring Truman to make his ultimate decision on relatively short notice.

Walker also examines the "full-scale invasion vs. atomic bombing" contention, and describes a number of alternatives then available to American policymakers. One, for example, was the softening of the demand of unconditional surrender from Japan. Another was to wait until the Soviet Union entered the war in the Pacific (which it did in the end, and Walker concludes that both the bombings and the Soviet Union's invasion of Manchuria were the two critical factors in prompting Japanese surrender).

To simplify a great deal, Walker ends with the statement that five considerations moved Truman to use the bombs "immediately, without a great deal of thought and without consulting with his advisers about the advantages and potential disadvantages of the new weapons":

1) ending the war as early as possible

2) justifying the costs of the Manhattan Project

(this one I was less convinced except for this bit):

If Truman had backed off from sing a weapon that had cost the United States dearly to build, with the result that more American troops died, public confidence in his capacity to govern would have been, at best, severely undermined.

3) gaining a diplomatic edge with the Soviet Union

4) lack of incentives not to use the bomb

(in summary: it was available, it was convenient, and militarily, diplomatically, and politically advantageous)

5) racism against the Japanese

(mostly contributed to override potential hesitation over the decision to drop the bomb)

As for my opinion on the rightness or wrongness of the decision? Berate me for moral distancing, but after reading this book...I honestly don't know. One thing I'd like to read more about going forward (which I have to, school paper and all, heh) is the strategic situation between the two countries, especially with regard to the U.S. embargo on exports to Japan and the attack on Pearl Harbor. Maybe a broader perspective would help.

reluctantly dnf'd, to be returned to later

EDIT: I give up. I try to take what I can get, but I'm sure I can find something better down the road, or return to this when I'm better read.

______

Page 117: For some reason, this slim little volume is turning out to be a huge slog. It isn't the book, it's me. I think there's one main reason, really.

I need to find a way to better anticipate a book's content. I came to this expecting a narrative history of the Qin and Han dynasties. Instead, what this actually does is organize content into a number of themed topics, almost completely disregarding chronology. This means a lot of generalized analysis on information I haven't managed to familiarize myself with yet, with very few references to specific events or details, so I struggle to understand the import of passages like this:

Scholars of the late imperial and contemporary China have noted that the practice of dividing households generally acccompanies a focus on marriage ties. Dividing households when sons marry emphasizes the conjugal tie, strengthens links with the wife's relatives, and elevates the status of the wife, who is protected by distance from her mother-in-law. Such quarrels between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law were certainly an issue in Han China, as shown in poetry and by the fact that a book of medical and magical "recipes" discovered at Mawangdui contains a spell to prevent the problem.

Whaaaaat.

Change of tactics: I'll try reading the chapters out of order, since chronology clearly doesn't matter in this book anyway. "The Outer World" and "Literature" look interesting, although judging off what I've seen of Lewis's writing style so far, it won't be much more than I've gotten already.

The sole chapter I've felt was helpful so far was "A State Organized for War." In it, Lewis describes how the Qin state's foundation of centralized military organization was the pivotal factor in its conquest of the other Warring States to form the first unified empire. However, a system made for conquest over rivals became obsolete when used to govern an entire state that had reached its farthest possible geographical borders. It helps that this section is actually grounded in historical detail, such as Shang Yang's reforms and the standardization of weights and measures, which really facilitates comprehension. I heartily wish Lewis had applied the same approach to the rest of what I managed to get through.

I've heard the volume on the Northern and Southern Dynasties is better, so I still might check that out.

The Queen of Attolia

I don't know what it is about this book. It actually seemed to get exponentially better with every sentence, all the way to the end.

At first, I was just struck by the tightness of the prose. Descriptive, witty, shifting perspectives without being overly coy. The occasional bits of humor are completely and totally deadpan. I expected the 3rd person POV to be a drastic change from the first book, but given that Gen was such a secretive narrator there, it hardly felt too different at all.

Once I reached the end, I couldn't help flipping back to fixate again on the many elegant turning points of characterization, conflicts between people who are equals in every sense of the word. Character tropes are all but nonexistent. We have two major sympathetic women in power. We have two sympathetic women in power with a sense of humor. Like, gee. When do we ever see that? More please!

The best thing ever

...I am trying to restrain myself from posting too much non book related stuff.

But.

Aamer Rahman (Fear of a Brown Planet) - Reverse Racism

Savor. The. Deadpan.

P.S. I never get sick of re-watching it, although it seems less and less funny each time. The first time I laughed until I cried. Now I just let the sad truth roll over again and again.

My Fair Concubine by Jeannie Lin

This is my third Jeannie Lin and competes with The Jade Temptress for stunning historical detail.

What surprised me the most was the element of friendship. There is an extremely thrilling villain who shows up in the middle, and Yan Ling and Fei Long standing shoulder to shoulder, facing off obstacles together to defeat the odds had such an air of camaraderie that I almost forgot it was a romance book, up until the obligatory sex scene.

To be honest, the love between them seemed a lot more like childish crushing, particularly on Yan Ling's side. Having grown up as something of a street urchin-ish, I did question whether she was capable of something mature, passionate, and long-lasting, particularly within the social stratifications of the time. In an alternate mental rewrite I thought it would make a great swashbuckler, with the two ending up as eternal best friends as opposed to husband and wife.

We have a wonderfully colorful secondary character in Bai Shen, who I loved because I recognized him. Or wish I did. The guy who sarcastically recites passionate romantic poetry, gives dramatic bows to everyone, *winks winks* when he sees you falling in love and pulls sneaky pranks just to piss you off--but has your back in your worst moments even after he's been rejected.

One thing Jeannie Lin captures really well is the prominence of legend in a cultural psyche. At one point the story of the Maiden of Yue is performed in theater, and I could imagine the excitement it must have had on Tang dynasty urban audiences just through a single scene. An archery contest near the end is literally modeled after the myth of Houyi, with Fei Long's legendary skill put to test in comparison to his former achievements.

The crowd began to whisper that down at the end of the line was a young archer who had not only hit every target, but whose skill and technique was as clean and fluid as a line of poetry. He wasted not one movement, not one arrow.

It seems by the Tang dynasty that martial prowess was increasingly giving way to civilian virtues, archery being popularized an aristocratic sport in the cultural eye rather than military skill.

Aside from that, the clothes, food, buildings, calligraphy was like walking back into time.

Looking forward to reading more of this very enjoyable author.

The Killing Moon by N.K. Jemisin

I think I read this book the wrong way.

I started out reading the synopsis and still having a very hazy idea of what it was about, which is not my usual style. I like to have some solid conception of the ideas, themes, and characters before diving in so I know ahead of time what to appreciate. For this, I just heard it was good. And that it was placed in an alternate ancient Egypt.

If appropriating "bygone cultures" is a habit of Jemisin's, I may very well continue to read her other works. Capturing the feel of a land that might have existed thousands of years ago, in a desert setting so unlike the world I live in, with the yearly flood of the equivalent of the Nile River, is something Jemisin does so well it takes my breath away. It's for this reason I also plan to continue reading Guy Gavriel Kay, and the thought of having found two authors willing to make historical imagination into fantastical reality is quite a delicious discovery.

Anyway though.

What made this fail to click with me, or perhaps vice versa, was that I wasn't prepared for just how earnestly Jemisin would take a story of personal religious questioning. I don't really, as an individual, understand what is required to sustain sincere faith. (If you're wondering, I am an atheist.) Maybe deep down I actually have managed to believe that institutionalized religion is stupid, backwards, and worthy of the utmost scorn. To take anything in complete faith demands too much vulnerability from me. But at the same time, I don't want to acknowledge that the rejection is partially irrational. At the end of the day, despite all its intellectual trappings, cynicism is a defense mechanism. We question things so we know where to throw up our walls.

So when Ehiru and Nijiri first walked onstage with their oh-so-all-encompassing dedication to Hananja (I think? Jemisin's mythology is so complex that a lot of it actually flew over my head), I laughed.

I thought to myself, wait for it. The sarcasm. The irony. The criticism. The satire. Come on, it's coming.

...

...

...

...

Ok, maybe not.

(Just to be clear, I didn't expect Jemisin to demonize religion so much as subtly undercut it. A simplistic portrayal of anything is boring.)

If anything, as the story goes on, Jemisin makes fun of the very thing I was expecting. The villain, to me, portrays the consequences of the loss of trust; what happens when you characterize the entire world you live in as evil, rotten, and corrupt, with nothing else sincere to hold onto. I might call it oversimplified, but I dunno how much it's my own bias as a personally rather cynical person figuring in there.

I guess every once in a while, a book comes along that challenges the very fundamental base of your worldview. This was one of them, and it does so in such a thoughtful, engaging manner that I have no choice but to respect it.

I'm still not sure exactly what I think of Ehiru's storyline, just by virtue of coming from way over on the other side of the spectrum, but this review does that excellently.

The Privilege of the Sword

Be honest: have you ever fantasized about your previously unknown, aristocratic, super-duper-wacky-cool uncle taking you, his niece, under his wing and teaching you swordplay? And using the subsequent skills to defend yourself and your friends from the villainous creeps of the world?

Your secret dream will come true for the four precious hours your face is stuck to the pages of this book.

Initially, I was enticed by the thrilling synopsis and the promise of a teenage girl's sword-slashing freedom (more like sword-thrusting). For me that was most of the suspense. Katherine's uncle makes a deal with her family: he will pay off all their debts if they send their youngest daughter to learn swordplay. We follow Katherine's journey, which culminates into only two major duels--but those are the payoffs, not the buildup. Those were the moments I held my breath for. And Kushner, contrary to my expectations of melodramatic Hollywood antics, maintains a tense--dare I say gentlemanly?--equilibrium that ended up being way more exciting.

With the privilege of the sword comes the power to challenge, to be challenged. To meet another on your own terms, whether they, or society, likes it or not.

I watched, and I responded. The crowd was quieter now. This was the way it was supposed to be, a conversation between equals, an argument of steel. I wasn't going to die. The worse that I could do was lose the bout, but I wasn't going to lose if I could help it.

This also resembles a novel of manners. There are codes of social mores, concerns about marriage, and money. In fact, the book opens with Katherine's going to her uncle's in order to save her family financially. One author on the back cover calls it a mixture of Georgette Heyer and Dumas, which though I've read neither, sounds fairly accurate. Kushner blends the two flavors so thoroughly that they feel part and parcel of the same world, even when not directly intersecting. Katherine's learning of swordplay, combined with Artemisia's husband-hunting, along a few others.

One of the things that surprised me was the Katherine's uncle, the Mad Duke. He takes something of a back seat and the role of teacher is relegated to three secondary characters. My question was, what kind of awesome weirdo sees his virtually-a-stranger niece's badass potential so unhesitatingly? In Calpurnia Tate, it's Calpurnia who seeks out her oddball grandfather of her own accord and earns his respect. At first, Kushner's explanation was that the Mad Duke was just a tad cracked in the head, but I wasn't going to accept that. As it turns out, this part is probably the most priceless piece of characterization in the whole book, and very subtly pulled off. Subtle enough that the pathos might even have been slightly dulled. But this is a rollicking adventure, not a deep emotional arc.

Ultimately, my favorite thing about The Privilege of the Sword is its concept. I love the combination of the traditional and the unorthodox, the way the story is structured to allow a girl to perform the heroics with all the right undertones of excitement, friendship, and accidental self-discovery. I hope Kushner's other books measure up, because I'm not sure just how much the plot concept played a role in my enjoyment, compared to all the disparate details added together. (There is some sex, which was interesting for historical-feeling context of prostitution and extramarital/bisexuality, but is written rather tonelessly.)

Hmmm...

A while ago I found out that China has a thing called the Twenty-Four Histories.

At first I was like, “Jesus, each dynasty had its own historian who wrote bazillion-page documentations of their period? Why don’t I ever know about this stuff?”

Anyway, I thought this would be super exciting to read, so I looked up translations.

Only two of them have ever been translated.

Gosh is that super infuriating. *shakes middle finger*

I am very, very curious to know why this is though. I mean, from common sense, most of our knowledge of imperial Chinese history would come from these works. Wikipedia even throws a vague statement about how “It is considered one of the most important sources on Chinese and culture.” If so…why only two translations? And why is one of them on a relatively ignored period? Do English-speaking Chinese scholars just read it and write their scholarly stuff in English without translating it for the general public?

Dying of curiosity over here.

EDIT: Actually, I found a translation of the Book of Former Han for the “Annals” section by Homer H. Dubs in the UCI library. Wow! So awesome. Maybe someday in the far future the rest of the whole thing will be translated too, for which I cross my fingers hard.

Ok, so far, I’ve combed through three libraries in search of Chinese history books. The vast majority of them are on 1800 and 1900 onward, focusing on the century of embarrassment in the Qing dynasty and Mao Zedong’s reign. It took me two hours to find a single narrowly-focused book (by that I mean, not stuffing 2000+ years of history into 300 pages) in the UCI library on imperial Chinese history. I wonder why this is. Why is it that Western scholars’ primary area of interest involves China at its most embarrassing moments when it began to interact with the Western world and was viewed as backwards, stagnated, and primitive? Did I just answer my own question there? I guess so.

Anyway, the main problem atm for me is this: it’s hard to tailor the resources available to my immediate interests/preferred style (mostly the actual fun stuff military history, major emperors, officials and generals.). I think what I’m unconsciously looking for is some direct and dirty analysis of specific events rather than an overview of general social and economic institutions. Or even comparisons with Western empires would be nice. Seriously, it’s not that hard to gather a bunch of common knowledge, sprinkle some occasional tidbits of high-school-level analysis, patchwork it together into a book, add some pictures and maps. Why don’t you just make the actual events the focus? I mean, I originally thought that the Chu-Han wars would get a lot of attention, being the big deciding conflict before the establishment of the first enduring Chinese dynasty that set the stage for the next two millennia, but nope…unless it’s Sima Qian. In general, I’ve found it difficult to figure out why certain details and time periods are not expounded on in proportion to their chronological importance. Which is very puzzling.

Still, the four scanty shelves of imperial history I found at the UCI library were so damn cool it was totally worth the two hours I spent searching for them. There was a full (I think) translation of Sima Qian, some volumes on women, and an individual chapter on Ming and Qing classical literature. Can’t check them out but I took some pictures of my favorite titles. And the resources for learning it might not be so narrow as I thought. Medieval Chinese Warfare 300-900 looks really interesting, so much so that I might actually buy it. Some potential exploration of previously barely-touched-upon people there!

Black Wolves

After letting this sit for almost two weeks...well. Still dunno what to make of it.

But whatever Jehosh might be, he did not have his grandfather's brutal possessive streak, the will to prevent anyone else from tasting a nectar he wanted to keep for himself.

Jehosh loved the pursuit.

His grandfather desired control.

Atani had carved a different path for himself, cut short far too soon.

For some reason, I loved parts like this. The legacy of personalities is something I find endlessly, hopelessly, eternally fascinating. Perhaps the most interesting thing about Black Wolves is the way we see the rise and fall-slash-decline of a kingdom in a single lifetime over the course of three generations, a story predicated on questions of legitimacy, suitability, and the possibility that the past might have gone in a different direction if a single individual had made a different choice.

It's also a big book. Structurally impressive, I thought, more thrilling than emotionally resonant. There's a 44-year jump near the beginning around the 80-page mark, a hole that is gradually filled through an interspersion of flashbacks. 200 pages in the beginning provide immersion more than setup, introducing a wide cast of disparate characters at different levels of society with diverging storylines. Focus for the people on the fringes is more on the personal than the political, with Lifka's jessing of a giant eagle, Sarai and Gilaras's arranged marriage. One thing that made the plot somewhat more difficult to follow was that those storylines seem to move wider and wider apart before coming together again, until I found myself entertained but not completely invested in Gil's subplot with

And then when that thread did enter a new turning point of sorts

(show spoiler)I wondered if Elliott couldn't have found a more succinct way to get there, and why

(show spoiler) needed to be dragged along.

The world is characterized by subtle sexism, not to the rape-y misogyny extent of A Game of Thrones but occasionally wavers close. There is also a brutal scene of male-on-male rape, an unusual acknowledgment in epic fantasy. Also some crass language and descriptions of bodily functions, so I hesitantly categorize this as "gritty."

In-world sexism shows itself in a number of ways. At its most thoughtful depiction it was quite deeply personal, questioning whether Dannarah would have upheld her father's legacy better than her brother Atani, and the way Anjihosh's inherent respect for his daughter's abilities was tempered by a stubbornness towards a preference for the son. Dannarah overcomes the obstacles of patriarchy to become the full-fledged woman she always wanted to be, but her sisters end up married off, destined for futures where their agency is tragically circumscribed but still put in positions that force them to fight for survival.

On the other hand, it also makes for a particularly cartoonish villain in Prince Tavahosh--the ultimate misogynist dolt whose face you want to claw to ribbons and has the unfortunate power to put his beliefs into institutional practice. Dannarah's final confrontation with him was too self-righteous to be complex, and I had to wonder again why such a conflict with so little thematic payoff was included in the first place, although that may change depending on how Elliott decides to develop it in the next books of the series.

Before reading this, I was told that Elliott could be depended on for the inclusion of women as important and fleshed out characters, and for the most part I found this to be true. Not only that but also women of all ages. Dannarah made a pretty awesome badass 60-year-old, and I'm desperately intrigued for the full story behind

I will say, though, that their personalities don't reach the full range as the males, with many of their lives sharply defined by patriarchy. Lifka is the exception and she felt almost gender-less at times, compared to Dannarah's more realistic struggles as a woman even in her teen years. Hers is an interesting story because it happens almost completely on the edges, and I'm left to wonder how she would grow as a person outside the forces of oppression against women in the central conflicts. Plus, her mysterious past opens a gateway to an entire foreign culture, which I hope Elliott will delve into in future installments.

The Cambridge Illustrated History of China

An overview of China from prehistoric times to the present that serves its purpose well. As with most histories, information density is weighted towards modern times, with a disproportionate number of pages spent on the Qing dynasty, early twentieth century and the People's Republic. Having said that, 2,000 years of imperial history still inevitably ends up with a lot of focus. Bigger emphasis is placed on wider patterns of growth and change than top-down political intrigue, with few individual names mentioned except for the major figures of the twentieth century.

Surprising amount of time was spent on the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, for what I thought was good reason: the first major diffusion of Buddhism, creation of institutions that the Sui dynasty would adapt to end three and a half centuries of division. Ebrey notes in an interesting statement that China very well might have split into two permanent kingdoms of north and south, just as the Roman Empire did into east and west, although it ultimately did not. One long-term impact of such an event is a cultural tendency to look on periods of division as undesirable, with the ideal state being "All-Under-Heaven" as a single entity.

One continuous theme is China's seemingly endless give and take with what they saw as "barbarian" cultures, that is, the various groups of people on China's geographical periphery: the Xiongnu, Xianbei, Tibetans, Jurchens, Mongols, and Manchus being the major ones in chronological order. I like how Ebrey analyzes their distinct relationships with China as the narrative goes on: the Xianbei, for example, ended up assimilating almost fully into the Chinese, while the Mongols resisted such integration and withdrew into their homeland after the fall of the Yuan. I also notice that Ebrey avoids taking a cyclical view while still describing a Chinese identity that managed to endure. It was especially during the period of Mongol rule--the first time an outsider ruled over a united Chinese empire--that the native Chinese were forced to question the centrality and universalism of their culture. Ebrey's overall view is one that empathizes with the perspective of the Chinese, without falling to the biases inherent to a nationalistic standpoint.

Quite thoughtful was the evaluation of the Ming dynasty, a period generally criticized as "a dead weight, slowing down innovation and entrepreneurship just when some real competition was about to emerge." While political administration was flawed, the Ming also witnessed a growth in population, trade, and publishing as well as an extended period of peace. Also notable was the development of full-length novels, producing some of the greatest Chinese works known today: Water Margin, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Journey to the West, and Plum in the Golden Vase.

Some fun memorable bits: Cao Cao--the main villain in Romance of the Three Kingdoms--and two of his sons were excellent poets, developing the potential of verse in lines of five syllables that would eventually be used by the most famous of Tang poets. And the two-page section on Dream of the Red Mansions really makes me want to read it. Just look at the illustrations, man!

Additional thoughts

The initial impression fades. It's quite masterfully written in its own right; the simple truth is that a relationship based almost 95% on sex just does not resonate with me beyond immediate visceral reaction. My preferences lean toward a mutual nurturing of emotional and intellectual respect, and I didn't really find it here.

The Dragon and the Pearl

For the lover of the steamy sex scene.

I must admit, I was not prepared for the fact that the majority of the story's suspense was sexual. It's just that, as a non-habitual romance reader, it's hard for me to grasp a relationship so deeply rooted in the physical. Nor can I imagine by even a light-year leap of empathy (at least at first) being attracted to someone who threatens you. How does that even work?

Once I got past that though, it was hard to put down. Because the relationship between two people takes center stage, you know what to focus on, what suspense clues to look for. The kind of tension that builds to a storm or dissipates in a heartbeat. As the story goes on, flashbacks reveal Suyin and Li Tao's pasts, and I found myself mesmerized by how their present personalities and harsh outlooks on life came to be.

Both have been brutally taught by experience not to expect much from their long-term futures, so the sex reads a lot like escapism. Grasping at connection, then returning to reality. Eventually, the emotional chemistry grows strong enough that it's worth preserving at any cost, with hopeful possibilities that they individually would never have dared to hope for.

Historical detail was awesome as expected, rich and colorful and culturally immersive. I smiled at the story of Sun Tzu's raising an army from the imperial harem, the emperor's delight that he and Li Tao share the same family name. One flashback shows that palace eunuchs did in fact pose threats to the women they guarded, despite their lack of sexual potency which gained the trust of the state, and it's all the more immediate because it happens to our main protagonist.

History is altered for the sake of story, the exact details of which are hard to describe without spoiling. Ling Suyin is taken from Yang Guifei, Emperor Li Ming from Xuanzong. Set in 759 A.D., the empire is in danger of fracturing in the wake of rebellion and a ruler's death. Warlords like Li Tao hold too much power, but transfer to central administration would leave the borders vulnerable and result in chaos. I would have loved for this book to expand into an epic political chronicle, but perhaps that's just a sign of how much Lin stoked my imagination with nothing more than backdrop.

Page-turning, but I seriously need a break from romance and will probably check out her steampunk series next. *whew*

The Truth-Teller's Tale

Quick and comforting read, cool concept, and cute romance. I have to say that I find the "you're secretly in love with me but you won't admit it" a really patronizing trope, especially when the female main character is dealing with entirely reasonable past issues of mistrust. The relationship between sisters is sweet though, and I loved that their loyalty to each other was held to the same importance as the romance.

Setting is standard medieval Europe, but set in the outskirts with a small-town feel (Eleda and Adele are the daughters of an innkeeper). Eleda's voice reminds me of Calpurnia Tate, in that it treats the everyday as something whimsical, which makes for entertaining reading for details that might otherwise have been dully cliche. I actually enjoyed listening to Eleda describe how she washed dishes! And the walks through the town during holiday festivals, with acrobats and food stands and theaters, were fun.

The Jade Temptress

A courtesan could scold, tease, argue. She could even use her tears if the need arose. Her arsenal was filled with every woman's weapon that existed, but the one thing she could not do was cause a man to lose face.

Quite possibly my favorite quote in the whole book, because if there's one thing the Chinese hate to death, it's "losing face." I was probably laughing hysterically when I read that. Except I also got to see it in a more exotic context, the tightrope a courtesan has to walk when playing with the men who hold power over her--usually men with a need to possess.

I have been going bloodthirsty for Chinese anything for a little while, and the discovery of the name of Jeannie Lin seemed perfect. It also helps that it looks like her novels mostly work as standalones, so I can pick and choose which ones seem the most interesting. This is the second in the series, but I read it first because of the allure of what seemed like a woman's sexual daring.

And it really does feel like it's set in Tang dynasty China, unlike GGK's heavily sexualized, heavily fetishized, somewhat Westernized version in Under Heaven. The correct honorifics are used, appropriate modes of address. There are fascinating hints at the complexity of the imperial bureaucracy, distinctions in social class, invocations of poetry and history in a world where sly verbal sparring is a dominant form of exchange. One reviewer said that reading Jeannie Lin was like watching a Chinese drama, and I agree. I wasn't surprised to find that the murder mystery was just as thoroughly researched as it seemed--Lin says that Wu Kaifeng's forensic knowledge is based on actual records of criminal investigations from the Han through the Tang.

And there's the way culture is woven into the structure of the story, too. The belief that destiny is the one who plays matchmaker. So strong that even the most twisted character in the story--Tang dynasty version of the creepy stalker, you might say--seems to share that belief, and channels every ounce of his willpower to make it come true.

On the flipside, it's Mingyu who realizes her dreams against all odds through a mutual growth with Wu Kaifeng--a romance that destiny seems to be working against. My only complaint is that I was hoping for a somewhat more epic confrontation with the main threat

who for such a full-fledged, powerful character gets put in his place a tad too quickly.

But for all that, it was a wonderfully written relationship, alternating between the clash of personalities and shared vulnerability. Threatened by outward circumstances, but steadfast--or maybe not?--internally.

Because this is romance, there is a strong undercurrent of sexual longing that culminates into a few sex scenes, all of which are of the bodice-ripping sort. Don't let that deter you, though. The main plot is a thoroughly puzzling murder case and I can safely say that there is no way to know what's going to happen. I cracked this open at 12:30 in the morning, thinking to get in a few chapters, and before I knew it I'd gulped down 60% and it was 4 a.m. with two hours left before I had to get up for school. I woke up two hours later with no ill effects and burned through the last 40% between classes before lunchtime, my face likely glued to the page. I can't remember.

My only regret is that I can't seem to find it in paper form, which I would really like to, cracked iPad screen and all. Still, I'll be searching for more Jeannie Lin with a ridiculously big smile on my face. I also secretly fantasize about what this book would be like if it were made into a Chinese drama...ok, never mind. *blushes*

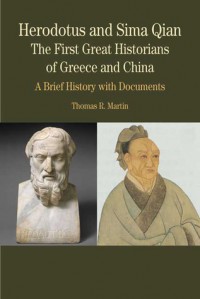

Herodotus and Sima Qian: The First Great Historians of Greece and China

I came to this much more interested in Sima Qian than Herodotus. Hence, I was very surprised while reading their excerpts that the style and tone of both historians were actually quite similar; content-wise, the basis for comparison was much stronger than I'd expected. In the introduction, Martin pinpoints their importance on the investigative nature of their writing--away from poetry and myth towards a more rational documentation of events--which paved the way for future historians of Herodotus's and Sima Qian's respective cultures to come.

This book is split into three parts: an introduction in which Martin explains most of his comparative analysis, a section of documents from Herodotus's The Histories, and a section of documents from Sima Qian's The Records of the Grand Historian, or Shiji. (By "document," I mean 10-on-average-page excerpts.) Each one is preceded by a short preface introducing the context, the people, and a remark on Herodotus/Sima Qian's approach. This piecemeal method of presentation--and the readable translation--worked well for me, since I find the idea of reading either historian's work at the moment a little terrifying, although I would like to do so someday.

Some of the most helpful information in the introduction were the notes on structure. Apparently, the exact method of organization for Herodotus's work is widely debated, but was groundbreaking in length and complexity, a factor that allowed for multiple digressions. Sima Qian's is divided into five parts: "Basic Annals," "Chronological Tables," "Treatises," Hereditary Houses," and "Biographies," presenting different pieces of information on the same people and events. This combined the approaches of the historians who preceded him: chronology, region by region, themes and cyclical patterns.

Excerpts included from Herodotus are mainly on the second Persian invasion of Greece (Thermopylae, Salamis, Queen Artemisia). Excerpts from Sima Qian are on the founding of the Qin dynasty, the early Han dynasty up to the death of Empress Lü, and stories on certain famous pre-imperial figures.

Since the rest of the book is made up of basically annotated excerpts, I won't get into them, except for one particular document that caught my attention.

While little is known about Herodotus's personal life, the comparatively more information we have about Sima Qian comes from the person himself. There is one document included that is not part of Shiji: a letter to a friend who would eventually be executed by Emperor Wu. In it Sima Qian describes how he endured imperial punishment so he could complete the historical work he had set out to do. When Sima Qian dared to criticize Emperor Wu for punishing one of his generals, he was thrown into prison and castrated--something considered even more shameful than death. Between the pain of having to choose between the honor of suicide and his life's dedication, the thought that his work would survive for future generations motivated him to struggle to the end.

I may have been fearful and weak in choosing life at any cost, but I also recognize the proper measure in how to act. How then could I endure the dishonor of sinking into prison bonds? If a captive slave girl can even take her own life, certainly someone like me could do the same when nothing else could be done. The reason I endured it in silence and did not refuse to be covered in filthy muck was because I could not bear the thought of leaving behind unfinished something of personal importance to me. I could not accept dying, if that meant that the high points of my writing were going to be lost to posterity.

And today, we have Shiji.

2

2

2

2