Jocelyn (The Reading World)

I love to read and can get very attached to my opinions, but recently I've been learning not to completely lose my head when people disagree with me, so feel safe to argue with me whenever you wish ;)

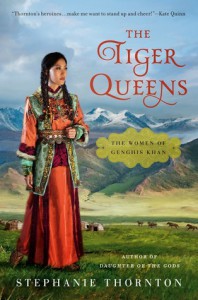

The Tiger Queens by Stephanie Thornton

I'm sure no book quite like this has ever been written before.

"I still carry the curse I once warned you of," [Borte] finally said. "Would you bring a storm of death onto the steppes?"

Temujin shrugged. "My strength in battle has already been tested. With you as my wife I will become a great and powerful khan, and our children will multiply and rule from the Great Lake to the Great Dry Sea."

Tiger Queens is a historical epic that stretches almost eighty years from 1171 C.E. to 1248 C.E. Timeline wise, the one that most of us are most familiar with anyway, this starts with the future nine-year-old Genghis Khan and ends with the crowning of his grandson Mongke Khan, placed three years earlier than the historical date for plot purposes.

But first and foremost, this story is one that belongs to the women. Which is why I read it (duh). They say that behind every great man is a great woman, and if this book isn't a splendid homage to that then I don't know what is.

Four perspectives placed one after another in succession: Borte Ujin, Genghis's empress; Alaqai, their youngest daughter; Fatima, a Persian captive; and Sorkhokhtani, Borte's daughter-in-law and mother of Mongke and Kublai Khan. The overarching plot driver is Genghis himself--who against all odds, survives his childhood, defeats his rival Jamuka, and unites the steppes before looking outward for civilizations to bring under his rule. But at home, it is the women who make sure his kingdom stays intact, and band together to rescue it when his male successors find themselves at each others' throats for the throne of the Mongol Empire.

The scope necessarily makes it an extremely fast-moving book, which is part of the appeal. The passage of time literally almost feels like the wind, quite appropriate considering how quickly the Mongol Empire consolidated itself from a group of scattered nomad clans to the largest contiguous empire in history. Time is especially condensed towards the last third of the book during Fatima's perspective. As the only foreigner in the group of four, her view is important because it's such an emotionally transitional one: as a new captive she's repulsed by the Mongols' barbarian savagery, before years and years pass and her thirst for revenge changes to the loyalty of a sisterhood.

Childless, and without a mother, father, or husband, I had no one in this world. Yet Toregene had been by my side for half my life, a sister not of blood, but of circumstance.

Second to Fatima, the most fascinating perspective for me was the first one, Borte's. I'm quite intrigued by Thornton's use of prophecy as an accurate plot predictor of death and destruction. It's definitely not enough to call it a fantastical element, but it's so eerily woven into the structure of the plot. Blessed with the gift of foresight, Borte sees that she'll precipitate a bloody war on the steppes, and this does indeed come true with Genghis's conflict with his blood brother Jamuka. Borte's POV also gives the largest coverage on the theme of sexuality, dynamics of gender, and the astonishing cruelty inflicted on women of defeated clans. With every conquest of her husband, there is looting and there is rape. Men are killed while women are absorbed, some whose new families extinguish the desire for revenge, some whose marriages give them newfound power comparable to that of their husbands'.

Alaqai's and Sorkhokhtani's stories are mainly ones of survival--the last ones standing. I should give a warning as Sorkhokhtani's section is surprisingly short, only taking up the last 60 pages or so compared to the hundreds of pages devoted to the three other women. It's no less important for that, in part because it was such a momentous point in history, and everything I'd ever assumed about Mongke and Kublai Khan as historical figures gets turned upside down when I realize that there was a mother behind the scenes biding her time and pulling strings. Thornton's author note at the end provides additional information. I'm more convinced than ever of Thornton's central principle--that the great men of history could never have accomplished what they did on their own without the help of women.

In sum, if Borte Ujin, Alaqai, Fatima, Sorkhokhtani, and Genghis Khan themselves were to time-travel to the present and read this book, I'm certain they'd be nodding their heads in enthusiastic approval.